There is whimsical, yet somber, air to the Roberto Clemente Museum in Pittsburgh. Off to one side, when you walk in, there is an iconic “Angel Wings” picture of the Pirates legend. It’s a fitting image of the man who was a godsend to many. Yet, roughly 40 feet away, there is a massive glass-enclosed piece of metal.

It is a propeller from an engine on the DC-7 plane that was supposed to carry Clemente on a humanitarian mission from Puerto Rico to Nicaragua. Instead it crashed minutes after takeoff on Dec. 31, 1972.

Duane Rieder, the museum’s executive director and curator, has had the propeller on display for roughly five years. Despite the fact that Roberto Clemente Jr. “hated” seeing the propeller from the plane that ended his father’s life it has remained. Yet, Rieder has formed a bond with the Clemente family over the last three decades since opening the museum, first as an archive, and then a fully functioning museum in 2007. More typical items like bats, jerseys and photos of Clemente are also on view.

Clemente’s birthday—he would have been 85 on Aug. 18th—and a recent visit by ‘LLERO to the museum, inspired us to share some of the lesser-known tidbits about Clemente’s life.

Clemente Hit A Historic Grand Slam

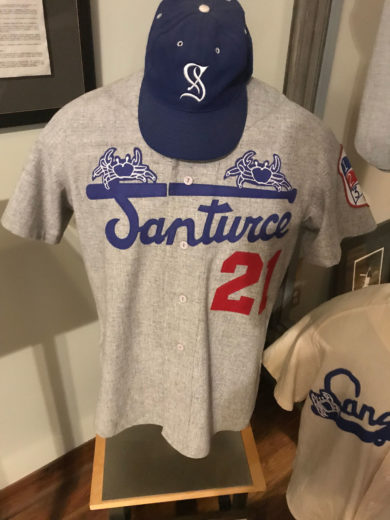

A replica Roberto Clemente jersey from his days with the Santurce Crabbers of San Juan, the team he played with in Puerto Rico. On display at the Roberto Clemente Musuem in Pittsburgh, Pa.

Clemente paved the way for Latin American ballplayers to be accepted in the major leagues. He was the first to win a World Series (1960), the first to win the MLB MVP (1966) and the first to win a World Series MVP award (1971). He was also the first to be elected to the Hall of Fame. This in large part to being just one of 11 players to reach the 3,000-hit plateau.

A lesser-known tidbit: Clemente’s the only player to ever hit a walk-off, inside-the-park grand slam, on July 25, 1956. No other time, in all of MLB’s recorded history, has this happened.

“He actually blows through the stop sign,” said Rieder, a Clemente fan and expert, of the play.

The “Angel” Photo Was Almost Lost

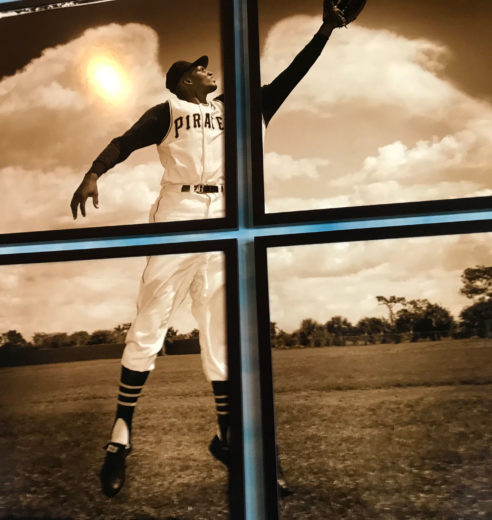

An iconic image of Roberto Clemente, with clouds behind him, that hangs in the Roberto Clemente Museum in Pittsburgh, Pa.

The iconic photo of Roberto Clemente framed by wing shaped clouds behind him almost never came to fruition. Rieder explained that the photo negatives were salvaged from a dumpster by an entrepreneurial man after two of Pittsburgh’s local newspapers merged and consolidated offices. Rieder eventually bought the negatives.

“It’s the backbone of the whole museum,” said Rieder, adding that the image was taken in Fort Myers, Florida in 1956.

Clemente was a Contract Negotiator

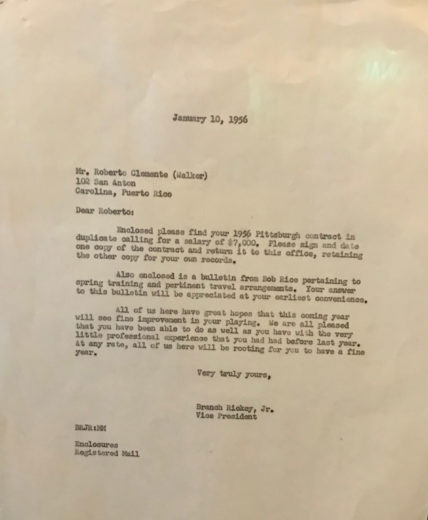

The original contract offer sent to Roberto Clemente from Pirate general manager Branch Rickey for his second professional season in Major League Baseball, on display at the Roberto Clemente Museum, in Pittsburgh, Pa.

When Pirates general manager Branch Rickey offered Clemente $7,000 for the 1956 season, he refused it. The correspondence of letters, displayed at the museum, included Rickey saying that “your request for $10,000 is an absurdity.”

After three fiery exchanges, Clemente penned a deal for $7,500 for that season. Still, that’s not even the most well-known Clemente vs. Pirates contract squabble. Little did he know what Clemente was really worth or how sports contracts would change in the future.

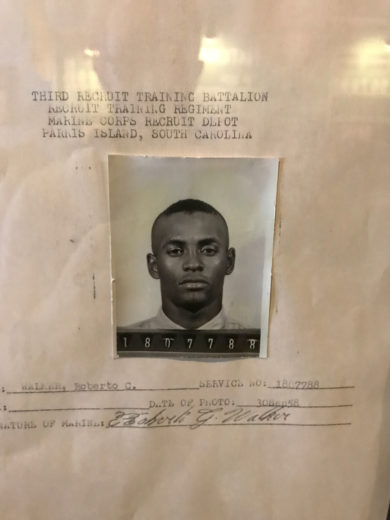

The Great One, Roberto C. Walker

Roberto Clemente’s original enlistment document and photo, on display at the Roberto Clemente Museum, in Pittsburgh, Pa.

After the 1958 season, Clemente enlisted in the United States Marine Corps Reserve. Clemente spent six months on active duty at Parris Island, South Carolina and Camp LeJeune, North Carolina. He spent a total of six years in the military as an infantryman. All of his military documents properly display his given last name “Walker”. This follows Latin American custom of children taking their mothers maiden name. Not until 2000 was this fixed in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

His Virtuous Humanitarianism

Part of the DC-7 plane recovered from the crash in which Roberto Clemente and others died, on display at the Roberto Clemente Museum, in Pittsburgh, Pa.

“Roberto was putting in 14 hours a day on the Nicaraguan campaign,” family friend Pearl Kantrowitz once told The Los Angeles Times.

When Clemente found out that supplies he had been sending to Nicaragua were being intercepted by The Somoza regime and not reaching earthquake victims, Clemente wanted to ferry supplies himself. His dedication to the cause led him to ignore warnings about the dilapidated DC-7 that fell from the sky. Teammate Manny Sanguillen missed Clemente’s funeral in San Juan. Instead, Sanguillen joined diving efforts to try and rescue or recover Clemente’s body, which was never found.

To visit the Roberto Clemente Museum, you can book a tour here.