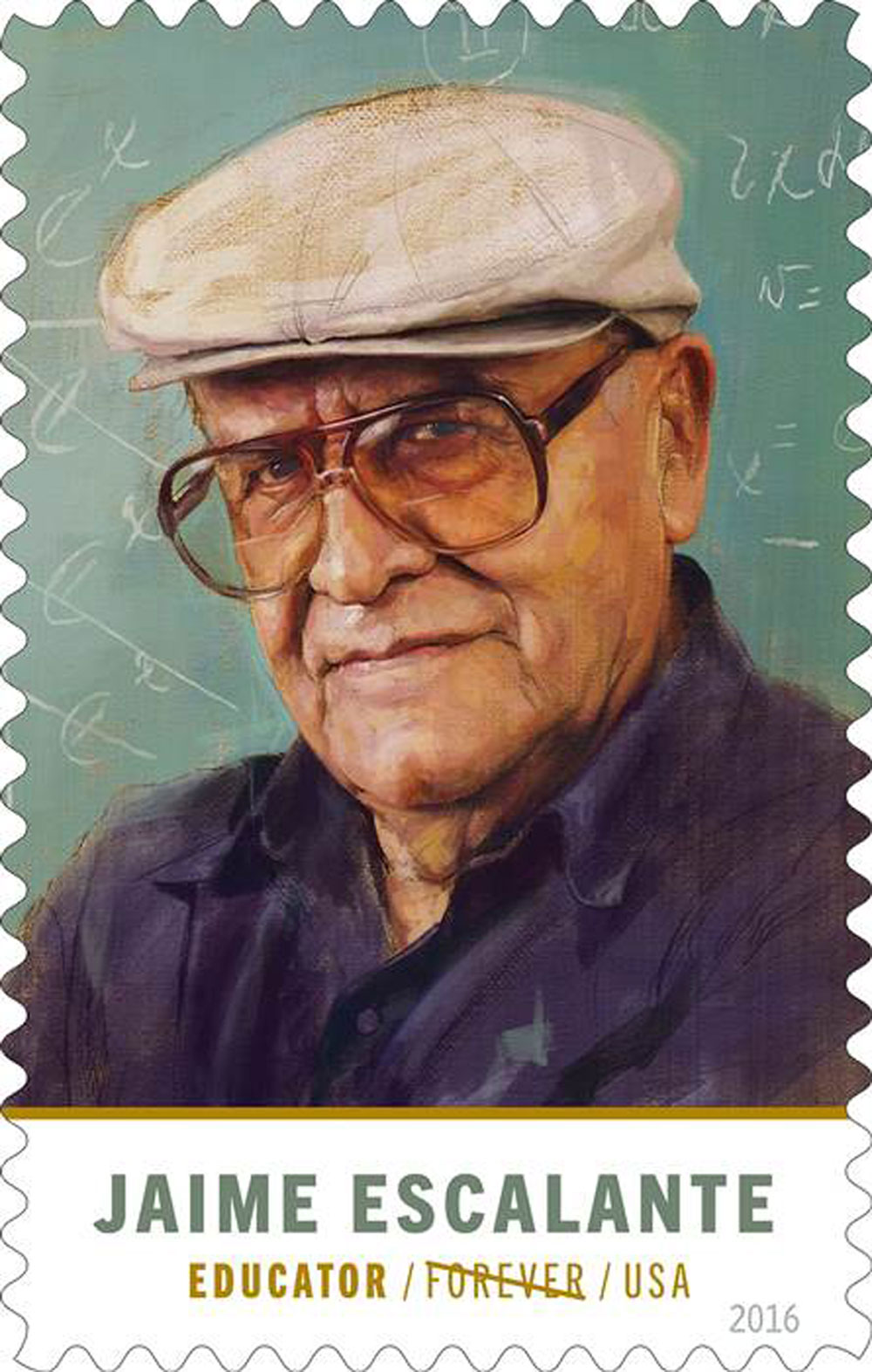

“You’re going to work harder here than you’ve ever worked anywhere else. And the only thing I ask from you is ganas.” – Stand and Deliver

While this concept isn’t new it took on new meaning thanks to Jaime Escalante, a math teacher who believed all students were capable of success if they had the drive to learn. This one man made the nation rethink how they looked at education in Latino and poor communities.

Jaime Alfonso Escalante was a Bolivian immigrant born to two school teachers on December 30, 1930. When his parents divorced his mother relocated Jaime and his siblings to La Paz where he attended a prestigious Catholic school and went on to serve in the military. When he started college at 19, his natural aptitude for mathematics and physics allowed him to become a science teacher although he wasn’t certified and hadn’t completed his degree.

In 1964, opportunity led Escalante and his young family, wife Fabiola and son Jaime, to California. It also meant that he was starting his life from scratch when he arrived. Despite being a veteran teacher in his native Bolivia, Escalante could not teach in the States. So he cleaned dishes and cooked in restaurants, while taking English classes, instead. He later took a job as an electrical technician but his passion to teach led him back to school. He earned an associate’s degree and then a bachelor’s degree from California State University Los Angeles and various teaching certifications so he could return to the classroom.

In 1974 he returned to academia at Garfield High School in East L.A., a primarily Mexican American school that was known for drugs, violence and underachieving students. He’d been hired to teach computer science at a place that didn’t even have computers.

While colleagues and administrators were desperate to keep kids in their classrooms he was intent on raising the bar through math. He believed that ganas and hard work would make children successful no matter their socio-economic background. “I’m trying to prove that potential is anywhere and we can teach any kid if we have the ganas to do it,” he was told the Los Angeles Times. Instead of teaching remedial classes he taught algebra, geometry and, after four years, his first calculus class in 1978.

Escalante was determined to get his students to take and pass the Advanced Placement Calculus test which would give them college credits. Two students took the test in 1978. Each year the classes grew and the number of students passing the AP did too. This was thanks to his drive. He recruited students the way coaches looked for athletes for teams; he required them to attend Saturday classes, get extra help in the morning, after school and even during their lunch breaks. Oh and then there was summer math classes. What started as an idea became an unprecedented Math program.