Contrary to what some people believe, Latinos are probably the most ethnically diverse group of people in the world. That diversity, unfortunately, comes with its fair share of inter-Latino rivalry and competition. Country of origin rivalries are perhaps the most prevalent yet the least understood. Many of these rivalries are rooted in history — past wars, territory and border disputes. You’ll see them manifest themselves in soccer games at times, where the rivalries find new energy in the quest for a trophy. Most of the time it’s healthy enough — root for your team, hoping for a rain of fire on the opposing players.

Tell Me If You’ve Heard This One…

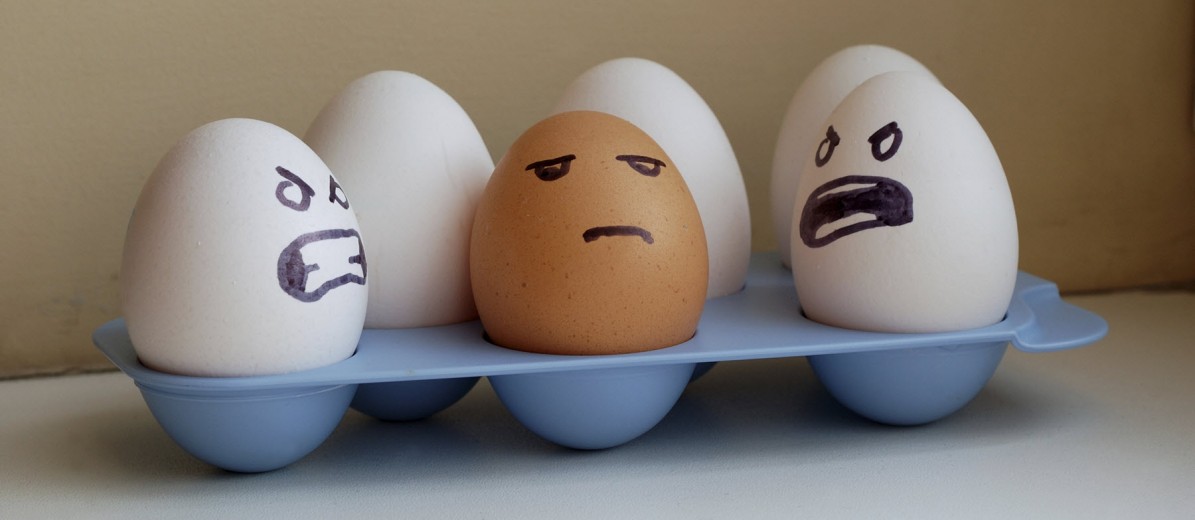

Sometimes it shows itself in a less productive way. Often Latinos place stereotypes on their own people of different Latin American ethnicities. I’m sure we’ve heard some, if not all of these:

- Puerto Ricans are ghetto. Dominicans are hicks. Argentines think they’re European whites.

- Cubans are con artists. Colombians are gangsters. Mexicans are probably illegal.

Without spending more time cataloging (and thereby perpetuating) examples, the point is made. Almost all of us have heard some version of these ridiculous characterizations. In the U.S., sometimes the rivalries come to a boil as communities live closer and closer together, especially in the urban areas, and often compete for the same resources like jobs, housing and political power.

But why would we speak about our own people from another land in such a negative way? The fact is, much of the rancor is cyclical and totally normal. It’s about first come first serve, and it’s been happening in the U.S. since the pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock.

It’s Origins

New immigrants have always had to contend with the so-called natives and suffer the hazing that comes with it. Before Latinos were even a U.S. phenomena the progeny of British immigrants were welcoming the incoming Irish with not only names, but downright violence (see the movie Gangs of New York). The Germans and Italians each had their turn at the bottom of the immigrant totem pole. Jump forward a century and West Side Story touches upon what Puerto Ricans dealt with when they became an established community in the Northeast in the 1940s and 50s.

A few generations later the demographics of Latinos in the U.S. is much more diverse than Puerto Ricans to the East, Mexicans to the West. The communities these pioneering Latinos once inhabited are changing before their eyes. In New York where Dominicans are the fastest growing Latino population and you can find more Mexican food stores in el barrio then cuchifritos. Older generations of Puerto Ricans are finding it hard to cope with the change. My own grandmother still sometimes says “dominicano” the way people used to say “cancer” or how some Whites say “Black”; in a whisper, as if the name somehow had shame attached to it.

Of course, I am married to a Dominican and have two beautiful Domini-Ricans, so I get to see how it plays on both sides. With certain members of my wife’s family, the fact that I can put two Spanish sentences together somehow amazes them, because Boricuas are seen as the “lost tribe,” absent of any real culture outside of the urban canon. I have a good friend who, when he visited the Cuban parents of his then girlfriend, was met with the question, “Por que me trae este negro a mi casa?” (Why did you bring this black guy to my house). Suffice it to say that was not a relationship that lasted.

The Prescription

I remember once walking with my soon-to-be wife in Miami Beach, where a nice, older Cuban man rented us beach chairs. When we returned his chairs, he walked with us back to the boardwalk and engaged in small talk. He asked where we were from. We responded with “New York.” “Ah, so you are Puerto Rican,” he stated with confidence. “Well, I’m Puerto Rican, my girlfriend is Dominican,” I told him. “Oh,” he responded. Apparently that was the end of the conversation. To this day we wonder which one of us caused him to feel like he could no longer talk to us.

What most of these anecdotes have in common is they reflect a generational disconnect more than anything else. I personally don’t know of anyone my age or younger, who perpetuates these divisions or believes these characterizations have a place anywhere outside a comedian’s tasteless joke. There is a generational shift away from “country first” and the understanding that we are all Americans, all Latinos, and that place of origin matters very little in this melting pot of a country.

I do believe that the era of inter-ethnic rivalries will soon be over. One reason is the globalization of information and technology. Facebook, Twitter and other social media provide us a real window into other communities that we have never had before, dispelling stereotypes before they even start. They also connect us with people of other ethnicities on topics like music, art, politics and what it’s like to be Latino in the U.S., not just Puerto Rican, Dominican or Mexican. Today’s wired youth are learning quickly that there are more similarities between ethnicities than differences and that those who perpetuate division do so for personal gain, above the community interests.

There are even ways to celebrate these differences, even to comic effect, without being hurtful. Heineken once did a brilliant radio campaign where they featured Latino men who supposedly had little in common: a soccer fan vs. a baseball fan, a reggaetonero vs. a norteño music fan. But both agreed about their taste in beer. Apart from the fact that this was a commercial about alcohol, it’s that kind of celebration of difference — with a unifying spirit that we need more of.

If you liked this article, check this one out: The Politics of Skin Complexion