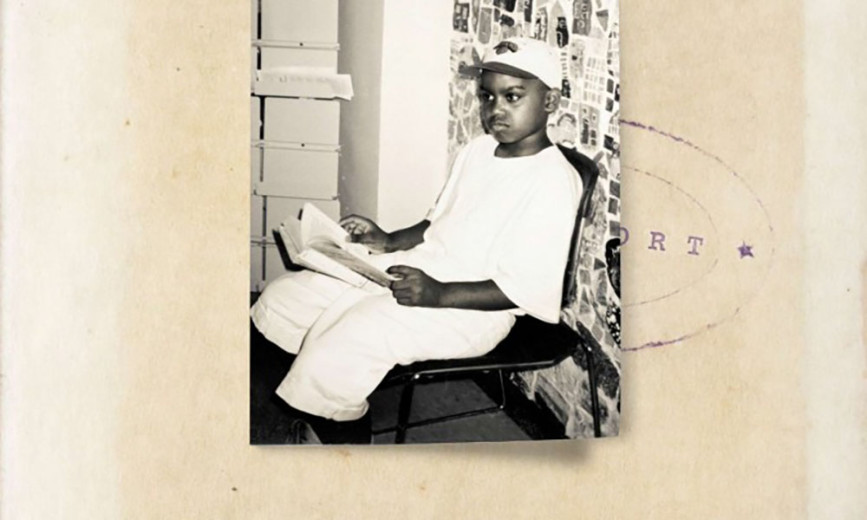

The world first met Dominican-born scholar Dan-el Padilla Peralta in 2006, when the Princeton University salutatorian’s undocumented status was revealed on the pages of the Wall Street Journal. Since then, he has become a rising star in the Classics field, earning his doctorate at Stanford and an additional degree at Oxford. Slated to join his alma mater’s faculty in 2016, he is currently a Mellon Research Fellow and Lecturer in Classics at Columbia University where his work focuses on the exploration of antiquity and the legacy of Greek and Roman ideals on the modern world. This past summer, Dr. Padilla Peralta released his first book, Undocumented: A Dominican Boy’s Odyssey from a Homeless Shelter to the Ivy League, a memoir which chronicles his journey from the streets of East Harlem to the privileged halls of Princeton. The 30-year old newlywed talked to ‘LLERO about why he believes Dominican race relations have Greek roots and the challenges that face young Black and Latino men in college and society.

‘LL: What was it about academia, and the Classics in particular, that drew you in?

Padilla Peralta: There are two overlapping motivations. The first is that antiquity is so capacious. I was drawn to a field that would enable me to be as multidisciplinary as possible. Within the Classics, you can do language study. A lot of the international scholarship that is being undertaken is written in French or German or Spanish or Italian. And I loved languages.

The second is due to the typical reaction I get, especially from Latino and African American friends has been ‘Well, why you would be a member of this field that has this pedigree of white superiority?’ And my answer is that in order to understand the full expanse of that and its implications, we have to study it. And I wanted to study it.

‘LL: What are some of the most common misconceptions or myths that you find that people have about antiquity and this ancient world?

Padilla Peralta: Maybe the biggest one is the idea that the Greeks and Romans occupy this space that is in the distant past. I’m using my work to show that the Greeks and Romans pervade so much of contemporary American and Latin American context that it’s very difficult to move within and through these spaces and not acknowledge the continuing impact of they had.

Years ago I learned that Santo Domingo was referred to as “The Athens of the New World” and I wondered why. In researching this I became aware of not only the colonial legacy behind that term but also how the positioning of the Dominican Republic as a state that had a claim to classical heritage was constructed to exclude Haitians from it. So we have writers from the Trujillato and after who are very explicit about this. So this has a far reaching impact on how contemporary Dominican political discourse has played out as well. We keep seeing these same ideas in discussions about how to treat Haitians and descendants of Haitians in the Dominican Republic today.

‘LL: How would you describe your book?

Padilla Peralta: My book is a coming of age story, about my experiences as an undocumented immigrant from the time of my family’s arrival in the U.S. to my college career as an undocumented student.

‘LL: A lot of your book deals with your personal experience navigating not just academic worlds, but also reality of modern urban life. People say there’s an invisible war on Latino men and men of color in general. How true is that?

Padilla Peralta: The war is real and the war is waged relentlessly against black and Latino men. One of the major insights of [Michele Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow”] is that each generation in American culture and American society has seen the evolution and refinement of tools for maintaining oppression. So when we talk about this war, one of the things that we need to be aware of is the intersections of how institutions produce this sophisticated set of mechanisms for maintaining systems of oppression.

‘LL: What do you see as some of the challenges facing Latinos–especially males-in college (if you can even find them)?

Padilla Peralta: One of the challenges is their relative absence and the difficulty of finding them, as you mention. One of the things colleges across the board need to do is devote more resources to increasing access to Latino males and other underrepresented groups. But, once they get on campus, there are challenges in finding people who look like them and who can model for them what it is to go through these spaces. So it’s important to provide mentorship in these places, but it has to take several forms. It’s not only a question of having administrators and support staff who are well-trained to offer that mentorship. We also need to diversify the professoriate and the higher levels of administration too. This is a commitment that has to be embraced by post-secondary institutions.

‘LL: What is it like navigating that system as a younger professor?

Padilla Peralta: The way I move through this space has changed because other people perceive me as an authority figure. But there are ways that my experiences are not all that dissimilar than what I experienced as a student. At faculty gatherings the level of diversity is lacking. This is particularly true in my field. In these spaces, I find myself speaking about how the nature and engagement of diverse bodies can be increased. On some level, as academics and classicists, [we] have to commit to doing something substantive about that.

‘LL: What advice do you have for someone who wants to pursue an academic career?

Padilla Peralta: I would ask them to take a long, sober look at the job market. I would also ask them to come to terms with a few things: academic work is lonely. It can be very isolating, especially the process of writing a dissertation and books. It’s not always the most comfortable thing. Then there’s [the] isolation that can be felt by men and women of color who enter disciplines heavily dominated by white men and women—the disciplines that have traditionally been the bastions of certain kinds of white privilege.

‘LL: What was the biggest mistake or regret you feel like you’ve made? What, if anything, did you learn from it?

Padilla Peralta: I wish that as a teenager I would have been more comfortable talking out some of the problems I was having. I felt so profoundly uncomfortable and so unwilling to do so, that over time it led to this build up of not only anxiety but also a kind of jadedness and cynicism that made it difficult to even be friendly to people in my life. And so, I have regrets about that and my tendency to keep my truest feelings from people was only something that I was able to sort out in my twenties and it took a lot of work.